Issue # 17 Adriana Ciudad

Curated by: Virginia Roy

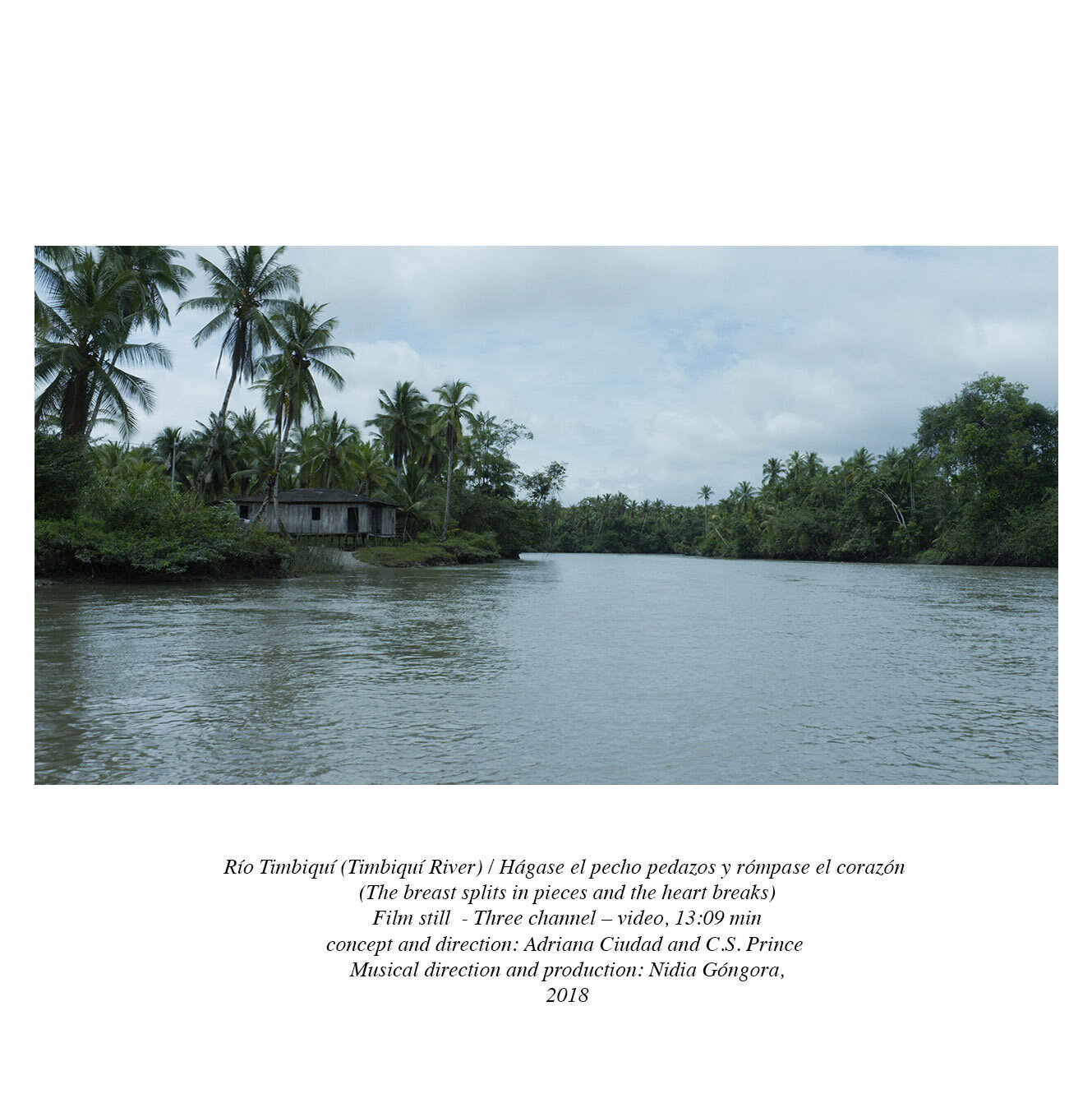

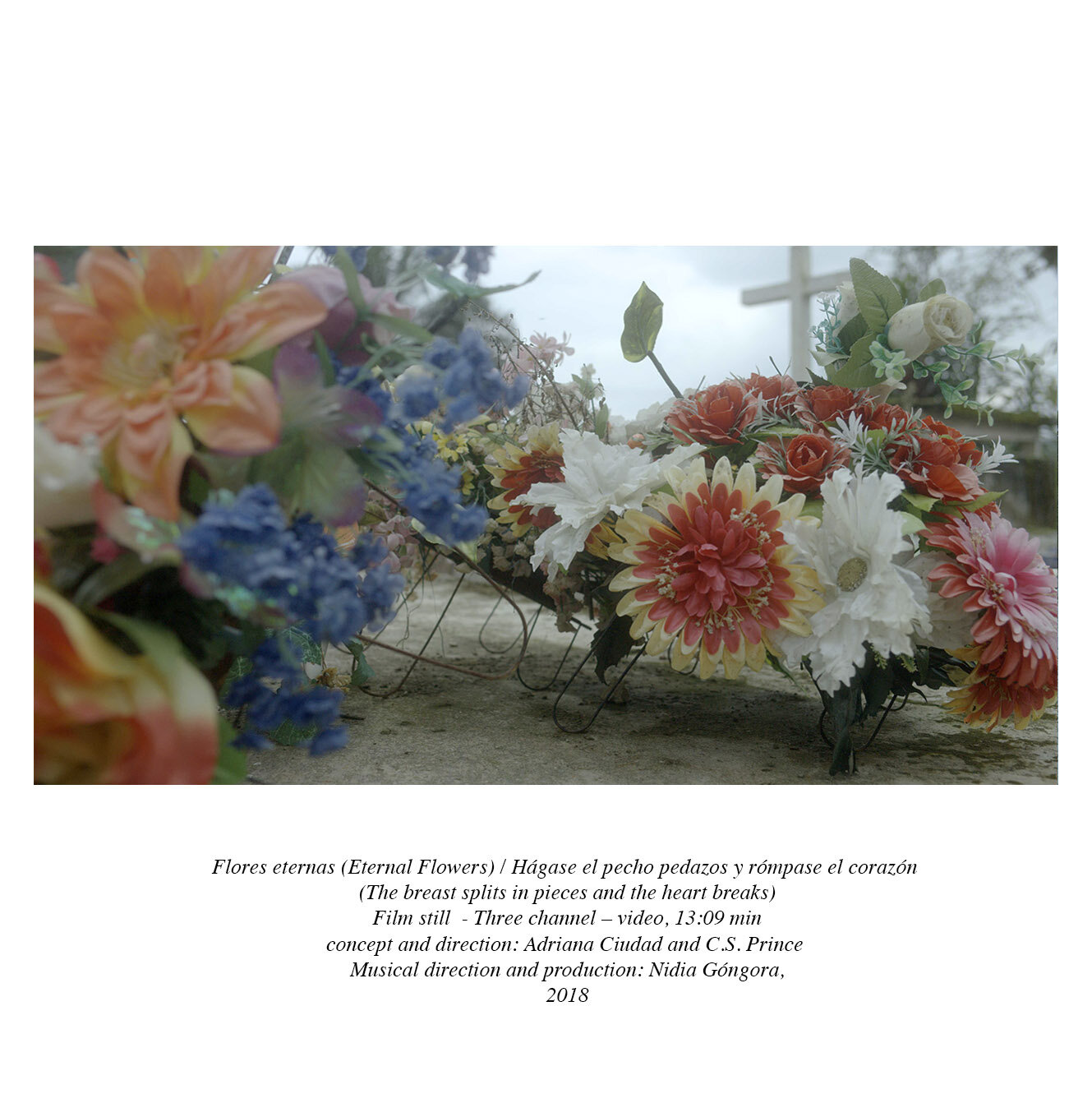

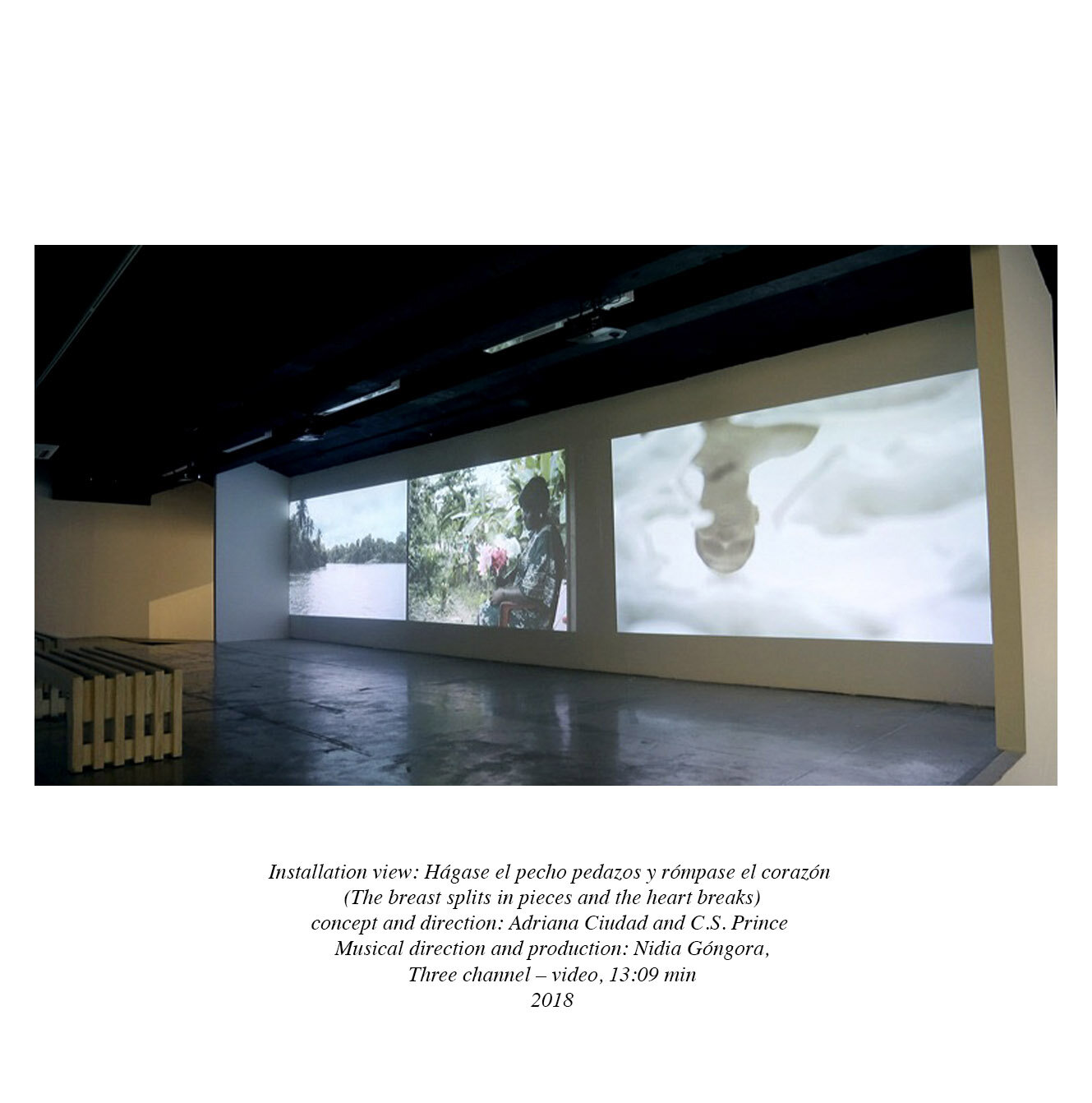

“Hágase el pecho pedazos y rómpase el corazón” (The breast splits in pieces and the heart breaks) Three channel – video, 13:09 min concept and direction: Adriana Ciudad and C.S. Prince Musical direction and production: Nidia Góngora, 2018

In December 2019, the first death from COVID19 appeared in China, a virus that we then saw as distant and that has been spreading throughout the planet, with millions of infected and more than a million deaths. If this pandemic has shown us anything, it is the fragility of bodies and the vulnerability to which we are exposed in an interconnected society. The celerity of death caused by the virus and the high possibility of contagion has led to the impossibility of a part of society to farewell their loved ones. In what way can we wake them and say goodbye? What are the rituals of mourning and grieving? Accustomed to a society of permanence, the loss of a loved one is an emptiness that is difficult to bear and his absence becomes unbearable and thrust upon us:

It is a day in which calm is nowhere to be found

In which the wind whips the window

a day in which the soul is wounded

and the eyes do not get tired of crying

The pupils are left without light and without glare

The throat is dry from so much shouting

the mind deranged, the heart perplexed

and gaze lost in infinity

In this context, the piece “Hágase el pecho pedazos y rómpase el corazón” (The breast splits in pieces and the heart breaks) by the Peruvian artist Adriana Ciudad has a special resonance. In 2015, Ciudad started a project with the cantaoras[1] from Timbiquí, a town located on the Pacific coast of Colombia that can only be accessed by river or plane. This community is closed and suspicious of visitors and its isolated geography has favored a strong sense of roots and belonging. Invisible, their populations suffer from precarious infrastructure, mining conflicts and also from violence and the presence of armed groups.

Timbiquí is also known for its population of African descent and for its strong musical tradition. Among its many musical expressions, the alabaos stand out, mortuary songs that in 2014 were declared Intangible Assets of the Colombian Nation. These millennial prayers are celebrated as farewell ceremonies for the dead, in a series of rituals that allow the family and community to say goodbye. As the singers say: "you have to sing to the dead."

Get up beautiful girl, get up and sing, so you can see how the mermaids sing in the sea

Alabaos probably originated during slavery, and their purpose was to finally grant them their freedom. These songs are generational learnings, transmitted orally, where the memory of the community is key. In fact, each community has a particular intonation depending on its geography. But above all, the alabaos are an example of cultural and religious syncretism. On the one hand, his African roots are manifested in the melodic and expressive capacity. And at the same time, the lyrics and the formalization respond to the Catholic religion. In the words of the singer Nidia Góngora: “The influence that the church has had in each of these manifestations is as important as the elements inherited from Africa and they remain latent in every scene of life in our territory: we see how the lyrics, messages, are oriented towards a theme related to saints, liturgies, all framed towards a Catholic context. But if we listen to the melodies, forms of intonation, interpretation and use of different melodic touches and ornaments, as well as satirical lyrics more linked to the profane, we find a very marked proximity to some African regions ”.

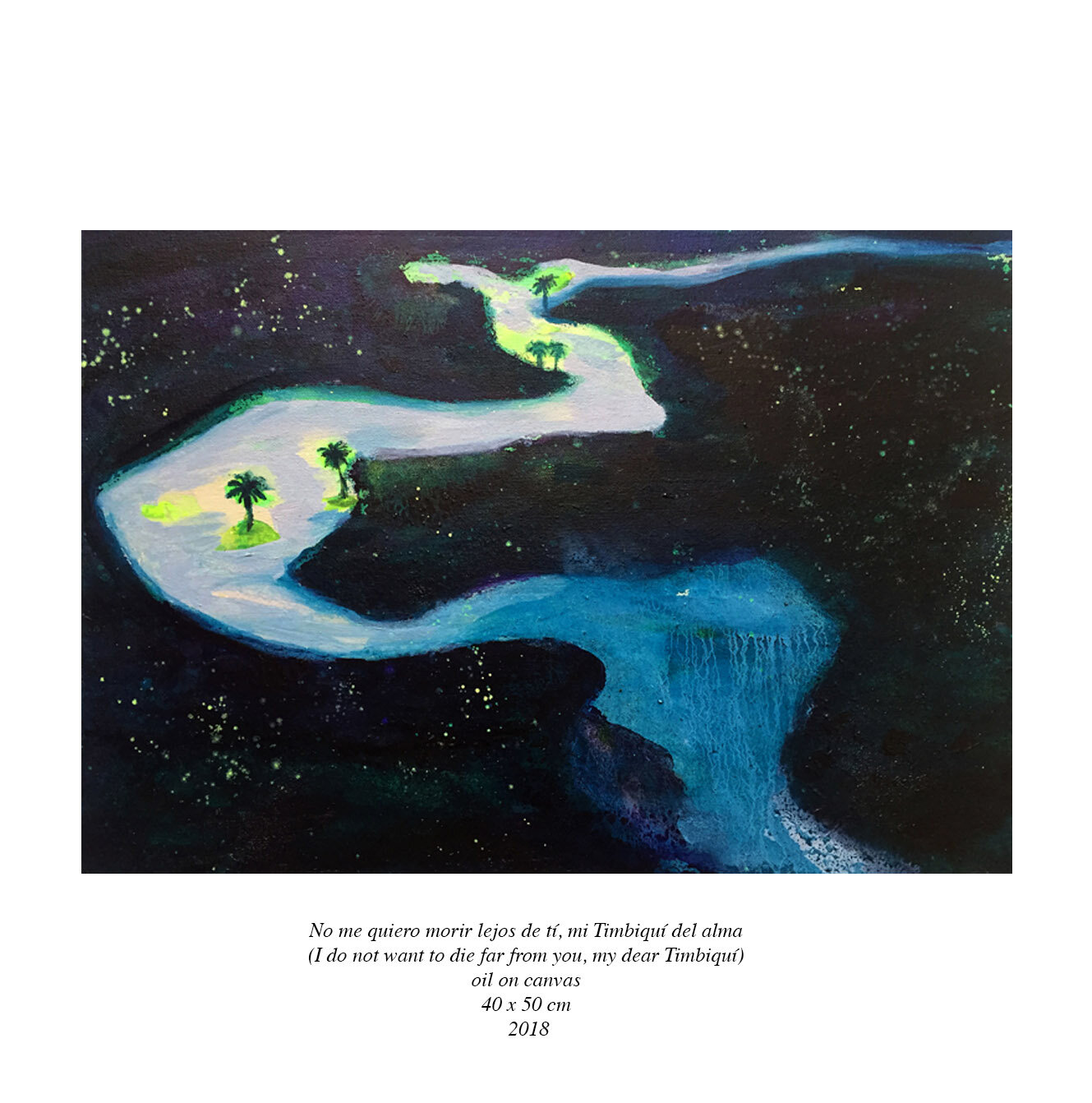

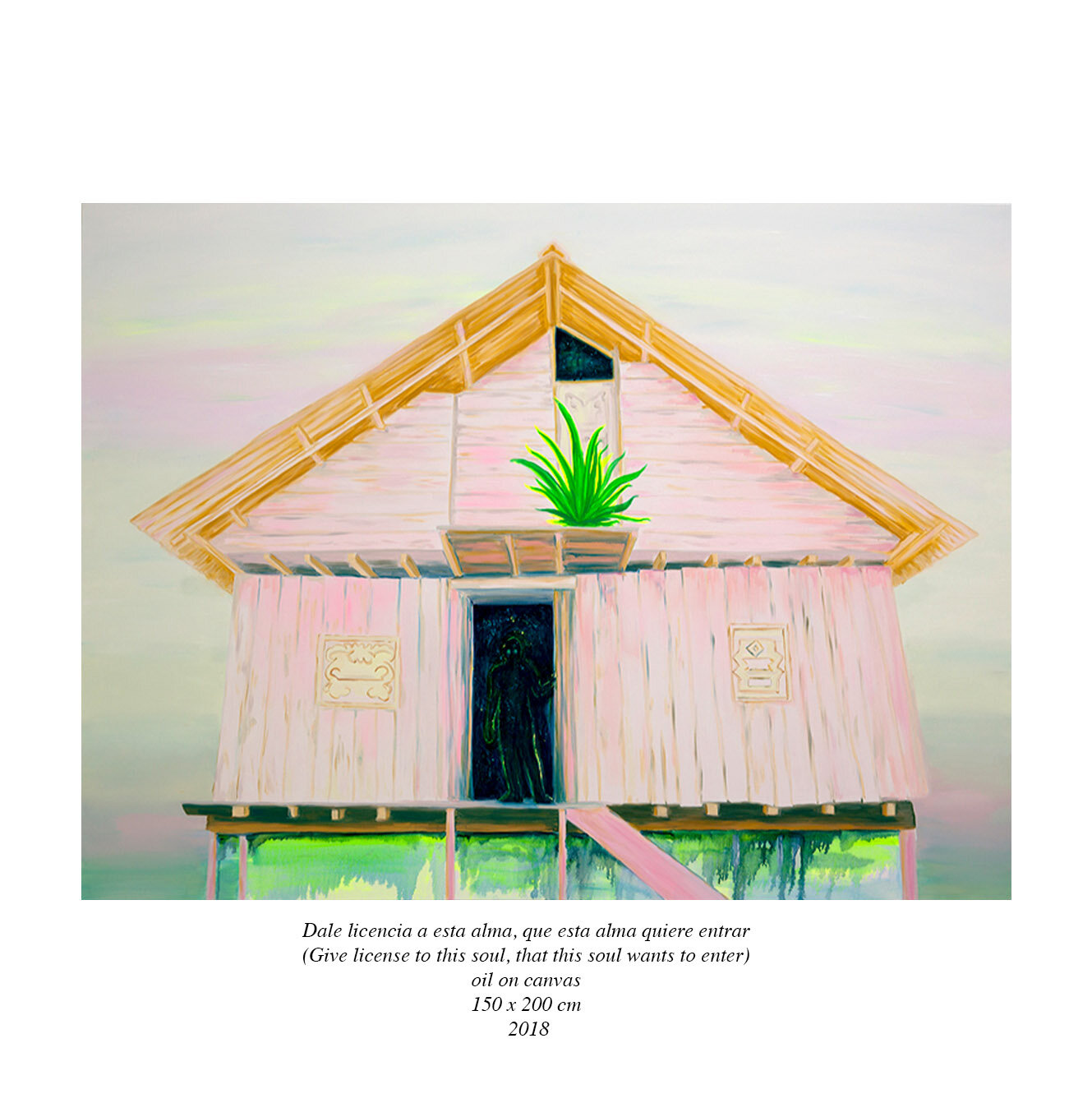

Adriana Ciudad came to Timbiquí precisely because of this singer, Nidia Góngora. The artist had just lost her mother and, upon learning of the alabaos, she came into contact with the singer and participated in the rituals that are only allowed to the population. As they say in Timbiquí, “if an alabao is sung without death, someone will die”. The result of Ciudad's research was the piece The breast splits in pieces and the heart breaks, a work made up of paintings and an audiovisual installation, whose title comes from the lyrics of alabaos. In the three channel video, Ciudad addresses the community's mourning rituals and, in a poetic way, presents a journey. Or many: the community’s journey of goodbye, the passing of the deceased and also the artist's own farewell.

Throughout the three channel video, Ciudad emphasizes the importance of the image to create a silent, sober narrative, where the only visual contrast is the color of the coveted plastic flowers used in the farewell ceremonies. Long-lasting, permanent flowers to pay homage to memory and absence. Together with the image of the art work and without any dialogue, what leads and guides us is the power of music as an articulator of the ceremony and the transit. A cyclical transit that begins in the waters of the river that takes us to the Timbiquí population, stops at the community's farewell rituals and continues metaphorically like the mouth of a river to the farewell of the souls. A sequence of rhythms and silences that take us on that journey.

How to communicate my pain with the pain of someone else? How to recognize ourselves in experiences of pain? Iliana Diéguez addresses these questions in her concept of pain communitas, where she superimposes the idea of communion proper to the collective with the need to communicate pain. Thus, the intimacy of individual pain can be recognized in the grief of the community and shared with common codes that allow loss to be brought about. The need and importance of mortuary rituals are a foundational part of collective social dynamics. In these rituals, the historical figure of the plañidera stands out, the weeping woman, one of the oldest funeral occupations whose origin dates back to ancient Egypt and which has lasted to this day. They come to carry me, those tears that cry. Known as yerit in Egypt or praeficas in Roman times, the woman (always the woman) cries to say goodbye to the deceased and give comfort to the family. Rivers come out of my eyes. Rip your chest apart and break your heart. My soul breaks and I lose my mind.

As in the rest of her production, Adriana Ciudad seeks to enter liminal spaces to see what constructions we elaborate as a society and how to rescue ancestral knowledge. Her artistic practice reveals the colonial structures and the hegemonies of power and knowledge that displace that knowledge. Ciudad proposes an exercise to make these buried traditions visible and delves into ritual as the formation of a community. At the same time, she understands affect as a political device and as a connection for the construction of critical subjectivity.

Recently the South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han wrote that we find ourselves in a communication without community, where the permanent connection of society separates us more and more as a collective, focusing on the individual. Han contrasts it with the community without communication, that society in which certain established and internalized symbols allows us to recognize ourselves as a community through rituals.

Adriana Ciudad's project is part of this concept. As a voice in the face of oblivion, her work stands to rethink the dynamics of coexistence that shapes us, and highlights the importance of the ceremony in this communion. Through the customs of the black community of Timbiquí, Ciudad emphasizes the need to say goodbye to a body, a being (in the words of the singers, a soul) to pay tribute and respite to the loved ones who leave us. To the land of oblivion. Following the funeral songs and their performative action, the ritual of the alabaos emphasizes the importance of closing, of farewell. As Han indicates, the challenge then is to understand that the we, acting in common, is a form of closure. Then, as the alabaos say, there we will see each other, without shadow and without face.

If death is to come

my life has to end

if the body is to be deprived

of pleasure and living

being infallible to die

Where will my soul go?

What will I feel when I see

What could I prepare?

standing to expire

sure death be

oh happy who employs

such hard trance go through

[1] A strict translation of cantaora is a flamenco singer, but in this context it means a special kind of singer.

* Sentences in italics are extracted from alabaos songs.

Virginia Roy

Adriana Ciudad Witzel is a Peruvian-German artist based in Bogotá, since 2014. Her most recent work has been exhibited in LA TERTULIA Museum (Cali), La Casa del Lago (Mexico City), Y Gallery (New York), SACO (Antofagasta) and in NC-arte (Bogotá). She was a recipient of the UNDP Grant (United Nations Development Programme) obtained to produce the Alabaos Project; a scholarship from the DAAD Programme (German Academic Exchange Service) obtained to carry out a project in Los Angeles; and the Painter Annual Prize of the Dorothea Konwiarz Foundation in Berlin. She has been Artist in Residence at Lugar a Dudas (Cali), and SACO6 (Antofagasta). Adriana Ciudad's work positions itself in a place where intimacy meets the collective. Using affection as a starting point, her artistic work intimately explores themes such as grief, childbirth, colonialism and ancestral knowledge marginalised by the Western paradigm.

Virginia Roy is graduated in Art History from the Universidad de Barcelona and she studied a year of specialization in Art History at the University of Sussex (UK). She completed the postgraduate courses Thinking art today at the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, and Social Management, at Pompeu Fabra University and Barcelona School Management. She has also graduated in Executive Training for Cultural and Museum Leaders at the Universidad Iberoamericana de México and the Institute of Leadership in Museums.

She worked in the Exhibitions Department of the Center for Contemporary Culture of Barcelona (CCCB) (2005-2006). From 2007 to 2014 she was adjunct curator of “la Caixa” Foundation, where she coordinated exhibitions such as: Sebastiao Salgado (2014), Art, dos punts (2013), Contemporary Cartographies (2012), Maestros del caos (2012), Omer Fast (2011), Pierre Huyghe (2011), Dalí, Lorca (2010), Chillida (2009), Rodin on the street (2008), among others. She has given conferences in México and Spain and published in several magazines and catalogues.

Since 2014, she lives in Mexico. In 2015 she was selected to curate the exhibition Limits Nomads at the Biennial of Borders, Tamaulipas. From 2016 to the present she is adjunct curator at MUAC where she has co-curated exhibitions such as Orden y Progreso, by Laureana Toledo (2015), Yishai Jusidman. Prussian Blue (MUAC / Museo Espacio, Aguascalientes / Yerbabuena, San Francisco / MARCO, Monterrey. 2016-2017), Gregor Schneider Kindergarten (2017), Ai Weiwei. Reestablish memories (2019) or Fritzia Irizar. Mazatlanica (2019). He has also co-curated projects in other museums in the country such as Memoria tísica. Edgardo Aragón, MACO, Oaxaca (2017) or Simon Gush. At the end of the work. Exteresa Museum, INBAH (2018).